The Torah: The Founding Fathers

By John Drane, Ph.D., professor of Religious Studies at Stirling University, Scotland.

The story begins with Abraham — or, rather, with his father Terah — in the city of Ur, at the very heart of the ancient Mesopotamian civilization. For some undisclosed reason, they left their home city and the whole family moved some 560 miles/900 km northwest to the city of Haran. Both these towns had important shrines for the worship of the moon god Sin, and some Old Testament scholars have supposed that this could explain their move.

There is certainly plenty of evidence to suggest that Abraham and his family were originally pagans. In a later account of the same events, a much later leader of Israel began his story of Israel’s history with the words, “Long ago your ancestors lived on the other side of the River Euphrates and worshipped other gods” (Joshua 24.-2).

Some have discerned traces of some sort of religious argument, which involved Abraham’s family in physical danger. For in a rather obscure passage (Genesis 1-5:7; Isaiah 29:22), Abraham is said to have been “rescued” from Ur in just the same way as the escaping slaves were later “rescued” (the same Hebrew word [hotsi’]) from Egypt (Exodus 20:2; Deuteronomy 5:6).

|

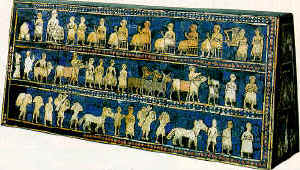

| The Standard of Ur, a wooden box inlaid with stones and shells, is from the Royal Cemetery at Ur, about 2500 B.C. This side shows the king celebrating at a banquet (top row), while servants bring animals and other goods as offerings (bottom two rows). |

|

| At Tel al Muqayyar, near the lower Euphrates River, the Ziggurat at Ur (above) once served as a three-story temple to the Mesopotamian gods. It was from Ur that the family of the patriarchs set out on their journey.

The fear and horror of men face to face with incomprehensible heathen gods and idols (below) find expression in the fixed, staring eyes of these nine statues, found in temple ruins northeast of Baghdad, Iraq. |

|

On the other hand, it is only in the Hebrew manuscripts of Genesis 11 that the city of Ur is mentioned at all. The Greek (Septuagint) version places Abraham’s original home “in the land of the Chaldeans,” and this could have been a place much nearer to Haran in North Syria than to Ur near the Persian Gulf. Other stories certainly suggest that Abraham’s roots were much stronger in Haran than in Ur, for when he later sent for a wife for his son Isaac, he told his servant to go to “the country where I was born” (Genesis 24:4), and this turns out to be not Ur, but the area around Haran [verse 10].

Despite this close connection with the town of Haran and its surrounding countryside, Abraham did not make his permanent home there. The book of Genesis tells how he moved on to a different part of the Fertile Crescent — this time travelling another 450 miles/700 km southwest, into the land of Canaan. There he lived a wandering life, moving about from place to place to find enough grazing for his flocks and food for his family. This was the only way newcomers could settle, for the best parts of the land were already occupied by both farmers and city dwellers. This explains why Abraham moved mostly in the south of the country [Genesis 12:9], just to the north and west of the Dead Sea. This was not the best land, but it had many areas suitable for grazing, and only a small resident population. When the grass was exhausted there, nomadic tribes could move either to an oasis like Beer-sheba or into the fields adjoining towns like Shechem and Hebron. No doubt this land was farmed by the Canaanites, but they probably allowed nomads like Abraham to put their animals onto it after the crops had been gathered. But even this source of supply was uncertain, and like many other nomadic peoples of the period, Abraham was forced to move as far afield as Egypt at a time of severe famine (Genesis 12:10-20)….

To us, it seems natural to want to relate Abraham to the social world of his day. But the central interest in the book of Genesis is not in the movements of nomads and refugees in the ancient world: it is in Abraham’s experience of God. His move from Haran was not determined by political and social issues; it was the result of a challenge and a promise made to him by God: “I will make you into a great nation and I will bless you; I will make your name great, and you will be a blessing…and all peoples on earth will be blessed through you” (Genesis 12:2-3).

Nor was this an experience unique to Abraham. It was also the common experience of his successors, Isaac and Jacob — not to mention the conviction of the rest of the Old Testament, that a personal experience of God was vital for the very survival of the whole nation of Israel. One of the reasons for our difficulty in placing the patriarchs historically is just the fact that the stories told about them are of a personal nature, telling how they met God in every circumstance of life.

For them, God was not a remote, impersonal force. Nor was he someone who must be approached only through the complex paraphernalia of religious rituals carried out in especially holy places. He was with them in the problems of everyday life, helping them to find wives and to have children, as well as meeting their deepest personal and emotional needs. It is no coincidence that for these people, the most natural way to describe God was to call him “the God of my father” (Genesis 26:24; 31:5, 29, 42, 53; 32:9; 46:1, 3; 48:3.5; 49:25; 50:17). For he was as close to them as their own family. Indeed, in an important sense, he was a part of their family: he was their leader, and they were his children. Unlike those who had a more settled existence, these wandering tribes were never tempted to think of their faith in God as something that was to be locked up in a temple or some other sacred place. It was something that went with them, and affected their everyday life wherever they happened to be.

This is why many later writers came to regard Abraham as supremely “a man of faith.” This was the great legacy of the patriarchal generation to the history of Israel. They were deeply committed to the belief that religion was of no value if it could do no more than produce a theology. It must be relevant and meaningful in the normal experiences of human life. In later ages, Israel was often tempted to forget this ideal, and to suppose that their God, like the gods of other nations, would be satisfied with the perfunctory performance of religious rituals.

But there were always those who were ready to call the nation back to the ideals that had been held by their ancestors, as they embarked on a new life and a new destiny with only God’s promise to guide them.

Text originally printed in An Introduction to the Bible, by John Drane, published by Lion Publishing plc, England, 1987, pp. 40-41, 46. Reproduced on this website with permission from Lion Publishing. In the United States, this text was published in Introducing the Old Testament, by John Drane, published by Harper & Row. Dr. Drane’s Introducing the New Testament is now published by Fortress Press.

Author: John Drane